THE WASHINGTON POST . SUNDAY, MAY 1, 2016

BY MELANIE D.G. KAPLAN

My beagle Darwin was no stranger to cross-country drives and adventures.

During her decade of life, she and I drove from East to West and back multiple

times. But one promise went unfulfilled. It was during her final days in 2011 that

we sat on the couch and I realized we’d never made it to the big beagle.

For years, friends had urged me to visit Dog Bark Park Inn, a whimsical beagleshaped

bed and breakfast. Given my adoration of beagles and appetite for road trips, the suggestion

was understandable. The only catch: Dog Bark Park is located nearly in the middle of

nowhere — in Cottonwood, Idaho, nestled between a couple of national forests in

the western part of the state.

Years passed, and I forgot about the giant beagle. But last year, when I began

planning a road trip to the Pacific Northwest with my former laboratory beagle

Hamilton, I realized our route would take us by Cottonwood. Having missed

the opportunity with Darwin and not knowing when I’d find myself in Idaho

again, I booked a room in the huge hound for early September.

The town of Cottonwood, population 900, is roughly equidistant from Yellowstone

and Glacier national parks, 41/2 hours from Boise. Right off the highway,

the tricolored piece of functional art known as Sweet Willy stands high above

honey-colored fields and looks out to the prairie.

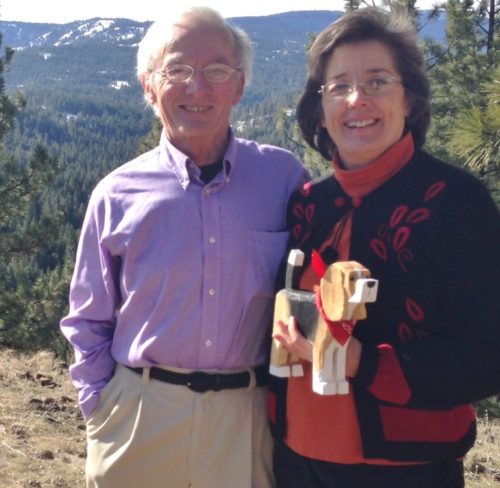

Artists Frances Conklin and Dennis Sullivan built the 30-foot beagle in 2003.

Dennis is a chain-saw artist whose big break came two decades ago when QVC

sold his canine carvings for 18 months. In the first 45 seconds, he sold 1,500 beagles.

He’d imagined using his profits to buy an orange Corvette and a new Ford pickup,

but after looking at both, as he tells the story, he instead opted to marry Frances

and buy the land on which their inn now sits.

I’d scheduled my stay in the beagle for the end of my road trip. Earlier in my

journey, while visiting pals in McCall, Idaho, I’d become fast friends with a

woman named Heidi. I invited her and her 2- and 4-year-old girls to join

Hammy and me in the beagle.

We arrived on a weekday afternoon and registered in a small, kitschy gift

shop that doubles as a carving studio. While Frances processed our paperwork,

Dennis walked out of his shop and welcomed us. He and Frances were

dressed in clothes a retired couple might wear for cleaning the house. They smiled

easily and radiated warmth and kindness. The front door was propped open,

and a dry breeze entered. The smell of pine filled each breath.

Painted wooden dogs—beagles as well as dozens of other breeds and the occasional

moose — lined the shelves. I met the couple’s dog, Sprocket, and was

surprised he was a golden retriever, not a hound.

“Why beagles?” I asked, after Frances gave us our room key.

“The beagle is the most beautiful artistically,” Dennis said. “If I did a black

Lab, it would just be a black dog.”

Heidi, her girls, my own aesthetically pleasing dog and I walked across the

property to the beagle and ascended near the hind leg. Steps led us to a balcony in

the rib cage area, where we opened a door into what in many ways looked like

a typical mid-priced motel room. We found the usual amenities — microwave,

hair dryer, etc. — but we couldn’t forget for a moment that we were inside a dog.

As if we’d fallen into a toy chest, we all poked around the room, discovering

nooks filled with books, games and snacks. A wooden ladder led us up to the

beagle’s snout, er, loft, where the kids found stuffed animals and a beagle book

that opened up to the size of a card table.

On the shelves and in an old suitcase were dog playing cards, puzzles and

Lewis and Clark bingo. Dog-patterned curtains covered the windows, and

wooden canines decorated the headboard.

I read the welcome letter, ostensibly from Willy: “If you hear muffled thumps

against my walls it ismy ears lifting up in the wind as a signal to you I am awake

and on guard outside while you relax or sleep inside.” Dennis had told me that in

60-mile-an-hour winds, the ears — made from enough outdoor carpet to cover a

few rooms — whip ferociously. The beagle body was made from lumber and

wrapped in metal lath, a bendable mesh, over which stucco was applied.

For dinner, we walked to Rodonna’s CountryHaus, a meat-and-potatoes joint

that’s one of just a few restaurants in town. We ordered food to go and picnicked

underneath the beagle torso. Between bites of their burger, the girls ran

around the grounds and explored other oversize chain-sawart sculptures (coffeepot,

toaster oven, fire hydrant) while Hammy begged for tater tots.

In the beagle, Heidi made microwave popcorn for the girls, and we all sat on

the bed with books. I flipped through “Barkitecture,” a book of fantastic doghouses;

and the “Carnegie Mellon Anthology of Poetry.” Heidi read the girls

“The Puppy Who Needed a Friend,” a small paperback with a gloomy, floppy-eared

hound on its cover. Later, as the girls dozed in the loft, Heidi and I stayed

in the belly, talking about life and travel and love.

Early the next morning, I went for a run through a ghostly quiet town, past an

American Legion post, the Cottonwood Elevator Co. (think grain, not vertical

transport), a body shop and a restaurant advertising “basket food.”

Back at the inn, the fiery sun had risen, and we set up breakfast on the balcony:

cantaloupe, grapes, homemade granola, eggs and canned fruit juices. Handwritten

notes labeled local cucumbers, Idaho rhubarb raisin muffins, and cranberry

and Idaho pear coffeecake.

Long before we were ready, checkout time neared. We packed our cars and

greeted Dennis and Frances in the shop. The girls plopped down on the floor

with wooden dog puzzles, and Dennis invited me to see his studio, a jumbled

space with a wooden “Puppy Mill” sign hanging from the ceiling and unpainted

wooden dogs — and sawdust — covering every horizontal surface.

As is often the case with travelers and dreamers, the four of us talked easily, and

the conversation quickly turned to the couple’s history. When they met at an art

fair in 1990, each was married with children. Dennis asked Frances shortly

after whether she had any room in her heart for him. Thus began a five-year

courtship through snail mail, and the two eventually left their spouses and

married in 1996. Frances, an English major, dabbles in poetry. As we talked,

she kneeled on the floor to help the girls with their puzzles.

Dennis talked to Heidi and me about following your heart and knowing when

you’re on the right path. Frances talked about solitude and time to let ideas flow,

as she experienced when she worked as a fire watch in Montana. Both used “love”

and “magic” repeatedly to describe their journey — and that of the Dog Bark Park.

In all my travels, people surprise me in wonderful ways, but perhaps I was most

surprised here. I drank up the couple’s words like those of a muse.When I caught

Heidi’s eye, we shared a knowing look.

Remembering the 450-mile drive ahead of me that day, I wrapped up our

conversation. Frances gently pressed a beagle stamp onto the back of the girls’

hands. I asked for my own stamp and then blew the ink dry. We all hugged

goodbye.

“Travel well,” Dennis said. “And live well.”

He and Frances stood in the door, waving. As Heidi and I hugged, tears

unexpectedly filled my eyes. Driving away, I looked at the big beagle in my

rearview mirror and the beagle stamp on my hand. Hammy slept in the back of the

car, oblivious to the thoughts swirling through my head.

Just outside town, I stopped for gas and read Heidi’s text. “I’m kind of in

shock and awe right now,” she wrote. “Thank you for sharing this time with

us!!”

I texted back: “Me 2. That was so much bigger than a big beagle.” I pulled out of

the gas station and followed S-shaped roads along the Clearwater River, in

silence, under cornflower-colored skies.

Kaplan is a freelance writer in Washington. Her website is melaniedgkaplan.com.